Nonprofit Program Design and Individual, Organizational, and Ecological Equity

Yesterday, I sketched out a holistic decision-making tool (as one does) about equity and work travel when designing programs such as national convenings and learning communities, which you can see below. It's a very rough, very drafty rubric, designed to support probing assumptions and decisions (mine and yours!), though it isn't designed to poop out a yes or no or rating in number form or something at the end.

Check it out and see what you think, and if you have a mind to, read the backstory and analysis that follows, which supports how I got to some of my thinking in drafting the tool. If you’re interested in getting a copy of the tool as a .pdf, you can find it here.

The Background

Life on the farm with Tim, left, and Theo, right. Photo Credit: Me.

Years ago – in 2001 – as I packed for a work trip, I was extremely stressed. I was a single mom, with a second-grader and a fourth-grader and virtually no support network. Since I'd adopted the kids two years before, I'd only left them overnight once, and that hadn't gone so well. Though a friend had graciously offered to babysit them for several days (along with my five goats, four chickens, three dogs, two geese, and one cat), she not only wasn't a farm girl, but she was in no way prepared for the physical and emotional labor that came along with caring for my kids over the course of several unstructured days. The boys had spent their formative years in foster care and, as I often say by way of shortcut, they had a lot on their plates. Taking care of them required a skillset that my friend didn't have – that none of my friends had. That even I didn't have yet, really. They were adorable, but a handful in a whole way that most people can't understand.

By 2001, the boys and I had left the farm and moved into a much easier (for me) arrangement. I was working as part of a very small educational technology startup, and the entire staff (all three of us) lived within a few hundred feet of one another. The boys and I lived in one half of a duplex a couple of blocks up from the beach. The other half of the duplex was our company's office. Our founder lived down the street, closer to the water. Our educational technologist, Evan (a former student of mine), lived across the street.

Every morning, after walking the kids to school I'd stop by Java Junction for a latte to go, and then settle in to work in my "home office" on my side of the duplex, which was connected by a door to the other half of the house. Evan would straggle over at some point in the late morning with a giant mug of soda and would settle in at his desk upstairs in the "work" half of the duplex. Our boss was often already up there, making calls and winning clients with his charm alone, since we didn't really have a portfolio of work yet. At lunch, we'd all go to the taqueria around the corner. In the afternoon, I'd walk to pick up my kids, stopping to dig through the ice cream freezer at the pizza place or score another Little Homie from Dave's Market. We had a chill routine, and most of our clients were nearby, or over the hill in Silicon Valley at the farthest.

That August, though, we'd somehow landed an amazing gig developing the architecture for a virtual learning community of sorts to support an arm of a complex federal agency that, naturally, was headquartered in Washington, DC. The founder and I were scheduled to make our first trip to meet with the lead, a no-nonsense woman who probably was more attracted to our low bid than my boss's charm, in mid-September. We were all a little nervous as we planned for the trip.

I was especially nervous about leaving the boys again, though this time I had several people lined up to pitch in so that no one caregiver got burnt out. And pretty much everybody was getting paid for their time. My boss and I were set to depart on a Sunday to fly into National for a Monday meeting followed by several days of additional on site work. By the week before, I had all of my childcare arrangements in place, with back-ups in case they were needed. I was paying for afterschool care and school breakfast (they usually ate at home) and lunch (which I usually packed for them). Various babysitters were walking the kids to and from school and staying for the overnights. It was going to be expensive, but I was pretty sure I had everything covered.

That Tuesday, of course, changed everything.

On September 11, I woke my kids up and fed them, and then walked them to school with the usual drama. But I didn't notice anything unusual at the elementary school. When I walked back around the corner to our street, however, Evan, up early, flagged me down from across the street and told me to turn on the tv. By this time, it was late morning on the East Coast: the first and second planes had already hit both towers of the World Trade Center in New York, and the third plane had hit the western façade of the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. The fourth plane had crashed into a field in Somerset County, Pennsylvania. Lower Manhattan was being evacuated, including over 1 million residents, workers, and tourists. It seemed like the world was set to end.

My kids were wired when I picked them up that afternoon, full of misinformation. France had bombed Las Vegas, according to my youngest. Though they knew I was going to Washington the following week, they hadn't really connected the dots. Even once they had, they weren't really sure what to think. On the one hand, I was the only parent they had. On the other hand, they'd each had several different parents (and a few in common) before me: parents came and went all the time. They weren't fazed, but still I wanted to cancel the trip. Even if their reactive attachment disorder was protecting them, they were still hyper-aroused. Their classmates and teachers were stressed, and they were picking up on that. Their caregivers would be stressed as well. It didn't bode well. I needed to be with my kids while the world was falling apart.

Photo Credit: Tech. Sgt. Cedric H. Rudisill/Department of Defense/Getty Images

But my boss had other ideas. He'd talked to our client in D.C. and she still wanted us to come if we wanted to come. The airline tickets and hotel were paid for, the rental car booked. In his mind, there was no reason not to go. In between prep meetings for the trip, I watched CNN as the days went by, checking airport statuses, watching video of the heightened security restrictions and their accompanying long lines, fantasizing about ways to "accidentally" miss my flight. But Sunday evening found me flying over the Pentagon, descending to National. My seatmate pointed out the gaping hole to me and said he thought he could still see smoke coming out of the building.

My boss had a rental car and stayed with friends, and I stayed alone in a hotel near Dupont Circle within walking distance to the job site. I shuffled through the days in an anxious haze, putting on a bright smile for the client, eating overpriced street food for my meals, and stressing out about the childcare bills I was coming home to.

The United States Marine Corps War Memorial (Iwo Jima Memorial)

On the last day, my boss departed on an earlier flight, and our client realized I hadn't seen anything but the inside of her building and my hotel room during my stay in the capital. Though it was dusk, she offered to drive me to the airport and show me a few of her favorite monuments from the car along the way. But when we got to Marine Corps War memorial, she insisted we both get out and look at it up close. As we approached the lit monument, she told me about her personal connection as a Filipino woman to the Battle of Iwo Jima, tears streaming down her face, and I could feel the complex layers of the trauma of the last week in every word she spoke, even though she didn't mention the September 11 attacks. In the car, I told her about my kids and how stressed I'd been to leave them, given their needs. It turned out she had raised her kids alone also, and she had so much compassion for my situation. She wondered why I'd chosen to come across the country given the circumstances, and when I explained that my boss insisted, she encouraged me to start thinking about my voice and personal agency differently.

And so I did. Once back in Santa Cruz, I started to say no more often, to stand up for myself. And it turned out that my childless, wealthy boss had no context for the financial and emotional stress his insistence on me traveling had caused me, and he wasn't interested in growing compassion for my position when it came to future work trips. Shortly thereafter, we parted ways.

The Analysis

Now, almost twenty years later, my kids are out on their own and the last few years have found me so often flying for work as a consultant that my husband Gordon calls the airport my "happy place." I've become one of those frequent travelers who recognizes local TSA workers and members of United ground crew. I have often enough set the alarm for 4am so that I can catch an early flight from SFO to LAX and be back in time for dinner. I earn upgrades and even so many miles that last year I flew round trip to England for just the couple of hundred dollars it took me to upgrade to a business class seat both ways. During tax time, when I'm calculating my expenses, I cringe when I see how many of my receipts are from airline carriers, airport vendors, and taxis to and from airports, not to mention hotel stays, hotel restaurant meals, and the never-ending cups of increasingly expensive fancy coffee. Still, that's the cost of doing business, isn't it?

But lately, like a lot of folks, I've been thinking about the other costs of travel. It started with thinking pretty generally about costs to our planet and the future of civilization.

A colleague I much admire -- Barnali Ghosh – and her partner, Anirvan Chatterjee, spent a year from 2009 to 2010 traveling around the world without flying in order to demonstrate our capacity to make it from point A to point B while doing less harm to our planet by flying much less. I met Barnali last year when I joined a board she was a long-time member of, and she's influenced me in many ways since then, chief among them that I am now more reflective about my ecological footprint when it comes to air travel.

Barnali Ghosh and Anirvan Chatterjee

More and more, I'm turning to Zoom instead of my United app when it comes to meetings, even meetings with folks fairly nearby. But when it comes to program design for statewide or national cohorts, I'm still trying to figure out the balance of face-to-face gatherings and online engagement. How many face-to-face meetings will the cohort need to jell? Can I really expect social bonding to happen virtually if I cut down the number of face-to-face meetings to, say, one or two, and make the rest virtual? Won't I be giving up a lot of control of the outcomes by not having us do our work in the same room, together? Is there even a platform that can support a real community of practice?

The more I think about it, the more I wonder, though, if we've been asking ourselves the right questions in making those decisions. I mean, my questions are missing some important words, like equity and planet and health. Shouldn't I be asking what it means, for instance, to design programs that require mandatory travel for people living with various disabilities? For people who can't afford childcare? For people more likely to get patted down (or worse) by TSA? And can I really say that the stuff that happens when we're face to face truly outweighs its contribution to the destruction of the planet? Where do I even get off with that!?

This is my friend Ludovic Blain, who can – and will -- tell you a thing or two about TSA pat downs. Photo Credit: Essence Magazine

While academics in some fields (shout out to geographers!) seem to be making headway on understanding and acting upon the ecological ethics of flying for conferences, in the nonprofit world, I haven't seen the same kind of advocacy for reducing carbon-based energy use. We convene a lot, and we seem to be far behind academia in making an organized effort to develop standards for reducing our carbon footprint through reduced travel in our day-to-day work, program design, and conferences and convenings.

While we can probably all agree at this point that small meetings can effectively and thoughtfully be handled on Zoom, more recently, for a current project, I was excited to get feedback that my potential ten to twelve participants from around the state would be more interested in participating through Zoom than they would be in gathering in person. Beyond concerns about global warming and climate destabilization, participants cited additional equity issues – particularly issues related to financial cost.

For instance, they told me, even when a foundation picks up your flight and hotel and gives you an allowance for meals, the per diem doesn't offset the extra costs associated with eating all meals out. The financial burden is compounded for those who have to arrange childcare, like I did for many years, or pet care in their absence. And those who don't live near airports can't just take a quick and cheap transit ride to catch their flight so often face parking costs that are not reimbursable.

In addition to the financial load, there are intellectual and psychological stressors. By the time we are back to our desks (or our job sites or our classrooms) we have the extra work that didn't happen while we were gone. In some cases, we pass these costs on to our organizations, and in some cases we and our organizations bear the brunt of errors made in multitasking while traveling, with personal, professional, and organizational ramifications.

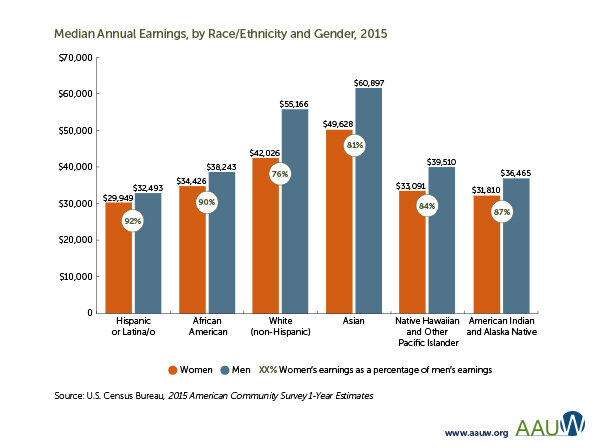

My potential participants reminded me of the gender differences, also, that should be applied when considering work-travel equity. All of my participants for this particular project are women, and, as we know, women as a class are paid less than our male counterparts. What's more, several of the women who I've invited to this focus group are women of color, who as a class are paid even less than white women.

Having to get an overnight babysitter, pay for a couple of $6.00 cups of coffee and whatever else your per diem doesn't cover was going to hit almost every woman in the group hard. Factor in that air travel and lodging reservations would probably need to paid up front, also, with reimbursement to come a month or more down the line, and what could be a run-of-the-mill work trip for some folks could become a nightmare scenario for others. When you are living paycheck-to-paycheck, a $500 trip plus expenses is going to require some juggling.

Graph: American Association of University Women

And then there's the whole global warming thing.

Last year was a pretty average flying year for me. I made about a dozen short roundtrips from San Francisco to Los Angeles and San Diego where I had clients as well as a several medium trips and trips coast-to-coast for training and conferences. Gordon and I also took a vacation to England. Using one of those online calculators, I estimate that my air travel for last year was about 17.55 metric tons (about average for an American) of carbon dioxide (C02), a major greenhouse gas. Comparatively, our household car travel (when I added in estimated taxi trips to and from the airport) only came out to 0.59 metric tons for the whole year.

Worldwide, flights last year produced an estimated 900 million metric tons of CO2, and that figure is anticipated to triple by 2050. While I was only one of 4.4 billion passengers carried by the world's airlines, for all my zealous recycling and attention to other types of consumption, I certainly was contributing significantly enough to the destruction of the planet by flying so much, and it bothered me.

And what about bringing my work "to scale"? I often design programs – convenings, learning communities, and small conferences – that require groups of people to fly to a location chosen often for the quality, price, or availability of its meeting facilities rather than estimated aggregate carbon load. I began to wonder how I might make more ethical decisions about travel in the course of my program design work. By designing programs that required tens and perhaps even hundreds of people to fly, I was racking up metric tons without even flying the miles myself. I was designing year-long learning communities, for instance, that were dispersing 185 metric tons or more of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere of our vulnerable planet! I want to take my work to scale, but not like this.

I think I can do better. I got my start in consulting in educational technology after all. I truly know how to create a supportive online atmosphere and curriculum for learning and the co-construction of knowledge, and I'm a great online moderator and facilitator, through text, live streaming, and video. I create learning objects, for Pete's sake. I once taught a course in Intercultural Communication that was completely online, with everyone in different time zones across the world, and it got rave reviews. I can do this. I'm not sure if my clients will be into it, but I can do this.

Thus, the rubric at the top of this post.

“I want you to act as if the house is on fire, because it is.”

While the rubric has lots of room for improvement and is still a draft, the planet hasn't got all day, as Greta Thunberg has reminded us, so I share it with you here in the spirit of give and take, and hope that you'll give me your thoughts and suggestions for improvements when you take a look at it.

I know I left a million things out, but I'm currently putting the sketch tool to the test as I work through my next project and hope to see how it supports (and doesn't support) decision making about the program design I ultimately propose to the client and funders. (By the way, if you've got great examples of virtual learning communities that you participated in, please share them with me so that I can share them in turn to persuade others to support this approach!)

Until next time!

Laurie Jones Neighbors is a research and strategy consultant who specializes in developing, implementing, and assessing programs in support of equitable political power and local, regional, and national decision making by low-income communities and communities of color.